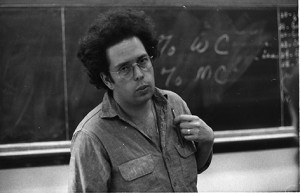

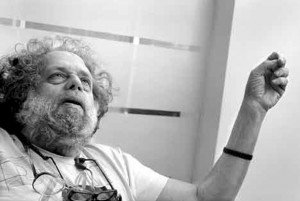

It was Marshall, whose aesthetic was wild, whose ideas were exciting, whose enthusiasm was contagious, and whose emotions were always on his sleeve. And yet, as vibrant and expressive as Marshall could sometimes be, there was a quietness to him that spoke volumes just as great.

By Jennifer Corby

Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science

City University of New York Graduate Center

Presented at

A Tribute to the Life of Marshall Berman

City College of New York

Friday November 22, 2013

I first came to New York to escape the suburbs, and the south. I was a secular, politically radical, vegetarian living in Texas, and I had done my time. I wanted to live in a place where public institutions were protected and promoted. Where the common good wasn’t sacrificed to personal morality. And where I could develop, rather than defend, my intellectual interests.

So I decided to move. And because, to my young mind, the most extreme option presented itself as the most logical, in the span of a few short months, I sold my things, said my good-byes, and bought a one-way ticket to New York. Considering how sensible these plans were, it may surprise you to learn that things weren’t so easy at first. There was so much to see in the city! But I couldn’t afford to do much more than look. I lived in a city of 8 million people! And yet I often felt alone. And I began to develop a nagging sort of feeling that I had exchanged one kind of isolation for another. But I really knew I was in trouble when I began reading Notes from the Underground, and found myself relating to its narrator, when he lamented, “I am alone and they are everyone.” When you find yourself empathizing a little too much with a Dostoevsky protagonist, it’s usually a bad sign.

But it wasn’t nihilism or self-pity that brought me to Dostoevsky. It was Marshall. In fact, Notes from the Underground was the first book that I studied with him, in a class called “The Irrational in Politics.” A class in which Dostoevsky, Freud, and Nietzsche loomed large, just waiting, it seemed, for the opportunity to really mess me up….but in a good way! With Marshall, it was always in a good way. Looking back, I realize that class played no small role in preventing me from succumbing to the fate of all of Dostoevsky’s characters, who learn about the transformative power of vulnerability and openness, but who do so too late. It wasn’t the Underground Man or Raskolnikov who taught me this lesson though; it was Marshall.

It was Marshall, whose aesthetic was wild, whose ideas were exciting, whose enthusiasm was contagious, and whose emotions were always on his sleeve. And yet, as vibrant and expressive as Marshall could sometimes be, there was a quietness to him that spoke volumes just as great. It was the patience, generosity, trust, and love that he simply embodied that allowed students like myself to receive and return his openness and vulnerability. In many ways it was the trust that Marshall showed me—trust I didn’t even have to earn!—that helped me to learn to trust myself and to take risks. It was in this class that I first fell in love with the exclamation point! By the end of the semester I discovered that I had developed a much more sensitive, strong, and creative voice. And it was in this class that I first got a glimpse of what a teacher and an education truly could be.

A few years later, when I began teaching at City College myself, I knew I wanted to try to give my students a similarly transformative experience. I wanted to show them the same trust and warmth that Marshall had shown me, and to help them learn to both understand the world and to articulate their many legitimate grievances and frustrations with it, but from a place of love. So we began with Socrates, a man whose playfulness and informal demeanor conceal an ethical commitment that is put to the greatest test. But sometimes Socrates can be a tough sell—it can be hard for students to relate to someone whose world seems so different from ours. And so we next read Martin Luther King, whose world is shaped by injustices that resonate today, yet whose message is much the same as Socrates—that to overcome injustice we must engage the world “openly, and lovingly.” A commitment as difficult as it is essential.

What Marshall shares with these two is the idea that justice and equality aren’t merely principles, but practices. Practices made possible by a kind of relationship we have with ourselves, one another, and our world. To this end, each understood education to be a process of self-transformation, whereby we become what we are. When I first came to New York, I was intellectually committed to justice and equality. But it was Marshall, whose demeanor was more that of a nudging horse than a stinging gadfly, that helped me to become the kind of open and loving person (and teacher) that these commitments required.

And in this process, I found and fell in love with the New York I had always been looking for—not only a place and a people, but a home.

Beautiful tribute. It captures Marshall’s spirit by testifying to its very material effects. thanks for this.